By Rachel Denyer (Penrose Antiques Ltd)

January 1797 in England started with violent winds and stormy seas. January 4th fell on a Wednesday and on that day Jonthan Chawner, a tanner from Horncastle in Lincoln, travelled to London to sign apprentice indenture papers with William Fearn for his son William Ch

to London to sign apprentice indenture papers with William Fearn for his son William Ch awner.[1]

awner.[1]

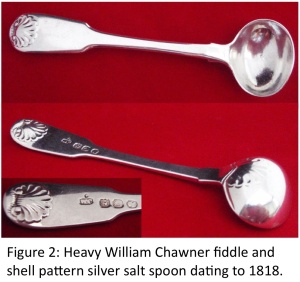

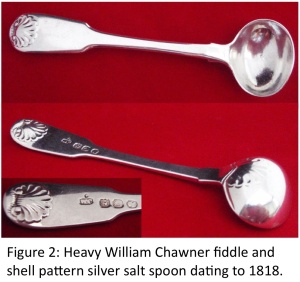

William Fearn was a well-respected silversmith known for producing quality flatware. 1797 also saw him begin a partnership with William Eley, and a joint makers mark was registered.[2] William Eley had done his own apprenticeship with Fearn in 1770. William Chawner’s apprenticeship must have gone well, because he joined Fearn and Eley as a partner in 1808, with a triple makers mark (Figure 1) being registered in that year[3]. This partnership continued until 1815, when William Chawner set up Chawner & Co (Figure 2), and moved into silversmith premises at 16 Hosier Street, West Smithfield in London which had formerly been occupied by George Smith.[4] On 16th June that year, William married Mary Burwash at St Bartholomew the Great[5]. The couple went on to have 2 children – William Chawner (b1817) and Mary Ann Chawner (b1818).

In 1834, William Chawner died aged around 51. His son William was just 17 years old, therefore his widow Mary took over the business whilst William did his apprenticeship, however it was not to be. At the end of the 1830s William Chawner decided against joining the family business, and instead chose to go into the Church. By this time, his sister Mary Ann had married, in 1838, to George William Adams. It was agreed that he would go into the business with her mother, and a joint makers mark was registered from March – November 1840. After this, George Adams took over Chawner & Co, and ran it exceptionally well. He was an exhibitor at the 1851 Great Exhibition and the company became one of the largest producers of top quality silver flatware in Victorian England. The Chawner & Co pattern book was published in 1875, and became the encyclopedia for Victorian flatware patterns. It was heavily referenced by Ian Pickford in his now-standard reference book on silver flatware.[6]

The 1881 census shows that George’s son, George Turner Adams (b1841) had also become a silversmith[7], and the subject of him taking over Chawner & Co must surely have been discussed. Maybe George Adams felt that his son wasn’t up to running the firm, or perhaps his son had indicated he didn’t want to remain in the business, as his uncle had done before him. Whatever the reason, George Adams sold the business in 1883 to Holland, Aldwinckle & Slater, and his son didn’t remain in silversmithing. By 1891, George T Adams had become a commercial handler of timber[8] and by 1901 a commercial traveller,[9] and by 1911 he was a commercial traveller and watchmaker.[10]

The 1881 census shows that George’s son, George Turner Adams (b1841) had also become a silversmith[7], and the subject of him taking over Chawner & Co must surely have been discussed. Maybe George Adams felt that his son wasn’t up to running the firm, or perhaps his son had indicated he didn’t want to remain in the business, as his uncle had done before him. Whatever the reason, George Adams sold the business in 1883 to Holland, Aldwinckle & Slater, and his son didn’t remain in silversmithing. By 1891, George T Adams had become a commercial handler of timber[8] and by 1901 a commercial traveller,[9] and by 1911 he was a commercial traveller and watchmaker.[10]

George William Adams remained close to his Chawner relatives. His brother in law William graduated from St Johns College Cambridge, and had a string of clerical appointments. He married in 1844 and had 6 children. William’s eldest son, another William Chawner (1848-1911) also went into the Church. A graduate of Emmanuel College Cambridge, he went on to become a Fellow, Tutor, Master then Vice-Chancellor of the college. Another son Alfred (1852-1916) went onto become a surgeon, physician and medical practitioner. The 1871 census shows both these nephews, then aged 23 and 18 respectively, residing with George Adams at 73 Addison Road, London[11] (Figure 3)

It was certainly a comfortable home, as the census shows the household included a cook, a housemaid and a footman. If Jonathan Chawner had foreseen the future family fortunes on that blustery January day in 1797 when he took his son to sign the apprenticeship papers, I think he would have been pleased.

[1] London Metropolitan Archive; Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/1282-1287

[2] Grimwade 3112

[3] Grimwade 3114

[4] London Metropolitan Archive, Records of the Sun Fire Office, MS 11936/468/906890 15 May 1815

[5] Guildhall, St Bartholomew the Great, Register of marriages, 1813 – 1827, P69/BAT3/A/01/Ms 6779/5.

[6] Silver Flatware: English, Irish and Scottish, 1660-1980 ISBN 9780907462354

[7] UK 1881 Census RG11; Piece: 61; Folio: 118; Page: 16; GSU roll: 1341013

[8] UK 1891 Census Class: RG12; Piece: 40; Folio: 92; Page: 31; GSU Roll: 6095150

[9] UK 1901 Census Class: RG13; Piece: 22; Folio: 67; Page: 31

[10] UK 1911 Class: RG14; Piece: 255

[11] UK 1871 Census RG10; Piece:35;Folio: 113; Page: 59; GSU roll:838760

This Blog is also Available via AntiqueStalker.co.uk